By Marie Solis

There are only a few things I’ve voluntarily waited in line to experience. To see the David, at the Accademia Gallery in Florence, Italy. To tour the Frida Kahlo home in Mexico City. To receive a COVID test a few times; at least twice for a vaccine.

Averse to hype and wed to some vague notion of “self-respect,” I have never waited in line for a Cronut, cupcake or TikTok-famous slice of pizza.

And so I had initially decided to close my heart to the latest trendy bakery, which regularly sells out of pastries like a matcha-mango morning bun, shakshuka focaccia slice and French onion soup croissant well before its official closing time.

Yet I could not deny my appetites. I love matcha, so I yearned for that bun. I was curious, too, about how the bakery seemed to of the zeitgeist between layers of laminated dough.

That’s how I found myself shivering on a sidewalk in Brooklyn on a recent April morning, questioning the nature of not just my own desires but also those of the three dozen or so people in line in with me. How had our tastes become so discerning? When did, say, a blueberry muffin start to seem a bit meager, less sophisticated, compared with the multihyphenate baked goods that we all appeared to be craving?

Somewhere along the way, I had unwittingly spoiled my taste buds. I was not a foodie, no. That identity category barely exists anymore. These days it is a norm, at least among those with disposable income, to have an ultrarefined palate and to embark on new culinary experiences whenever possible.

I just happened to be another person alive in our overdetermined era of hyperflavour, in which many of us seek out increasingly elaborate combinations of ingredients and spices to satisfy — what exactly? A drive toward indulgence? An anxious need to project a certain worldliness to our peers? Maybe, like a hojicha maple miso cookie, it’s many things at once.

We might worry it was a sign of an empire in decline if we were not so busy savoring all of this complexity.

It was 2020, and I was on my phone — more than usual. I was watching recipe videos on YouTube and admiring loaves of sourdough bread on my friends’ Instagram pages.

Like any coastal millennial worth her salt, I was also growing scallions in glasses of water on my windowsill and making Alison Roman’s caramelized shallot pasta. My roommate, who had temporarily lost his job in fine dining, taught me how to fold a dumpling and make a Last Word cocktail. Confined to our apartment, we were in pursuit of novelty and feeling.

The pandemic is a big reason for the way we eat now, said Bettina Makalintal, a senior reporter for Eater who started her popular Instagram account, @crispyegg420, during the early lockdowns. Her first post featured a piece of buttery sourdough toast, wilted kale and a sunny-side-up egg with dollops of chile crisp, a condiment that quickly became a staple of quarantine cooking and started appearing on big-box grocery store shelves.

It was just the latest addition to an arsenal of pantry items that the home cook had been slowly accumulating over years as hit cookbooks like Yotam Ottolenghi’s “Jerusalem” and Samin Nosrat’s “Salt Fat Acid Heat” introduced many people to new ingredients and ways of building flavour. At the same time, food publications like Bon Appétit and New York Times Cooking had begun to establish a larger presence online.

Once the pandemic hit, novices like me became unwitting food content creators, sharing their culinary experiments on TikTok, influencing one another and iterating on as they spread across the internet. In this increasingly flavour-curious environment, cooks from Asian and Middle Eastern diasporas found a wider and more receptive audience for ingredients that had long been staples in their kitchens.

“Adding an ingredient that’s perhaps, air quote, unfamiliar to some people is an easy way to riff on a viral recipe,” Makalintal said. “If tiramisu is having a moment on TikTok, then you might see someone doing matcha tiramisu or ube tiramisu.”

That’s a tried-and-true formula for creating dishes that feel au courant, according to Nick Palank, the marketing manager at Beck Flavors, which develops flavour profiles for clients in the food and beverage industry.

Based on its trend research and flavour development, Beck Flavors, a family-run company in Missouri that has been around since 1904, declared miso caramel one of its flavours of the year.

“We’re a meat-and-potatoes country here,” Palank said. But even in the middle of the United States, consumers are looking for more adventurous flavours: “More cultural, ethnic and specifically Asian flavours are doing really well. People want to experience the world without leaving home, basically.”

Those flavours tend to resonate especially strongly if they pair a nostalgic ingredient (caramel) with one that may be more novel, at least to a white consumer (miso).

“We’re getting away from the boring flavours, for lack of a better word,” Palank said. “Hazelnut, French vanilla, coffee.”

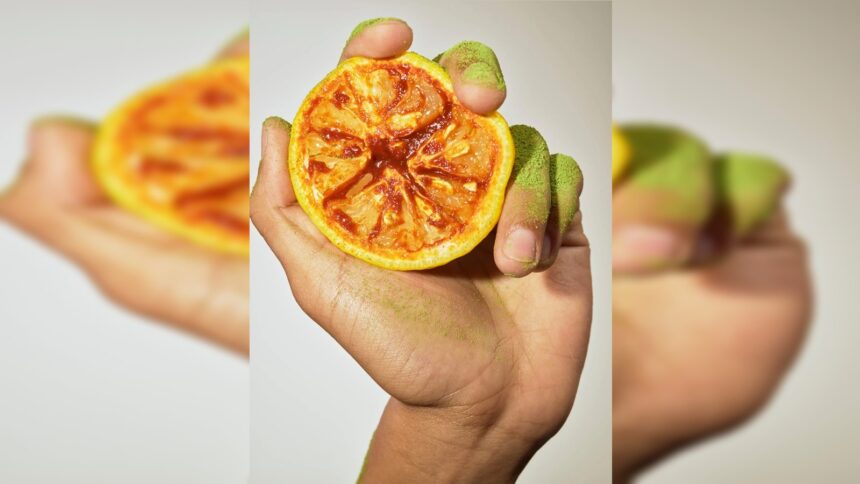

Once I began to pay closer attention, baroque flavour seemed to be everywhere. At Starbucks, I noticed an iced lavender cream oat milk matcha had returned to the menu for spring, along with a new iced cherry chai. For the erudite seltzer drinker, my local bodega had options like calamansi, hibiscus and rose, and Guava São Paulo, the favorite LaCroix flavour in my household as of late.

Out of curiosity and probably masochism, I decided to stress-test my palate. How much had it grown accustomed to hypersaturated flavours? And how much could I flavourmax before I maxed out?

I emailed Palank and asked if he and the flavour scientists at Beck could design a menu that reflected the tastes of the moment. I told him my boyfriend and I were planning a small dinner party for two of our most discerning friends in all matters of taste, Kevin and Dilara. I would need concepts for a cocktail, an appetizer, a main and a dessert.

A few days later, Palank sent along a four-page document with several options under each heading. Reading some of the menu ideas gave me a vertiginous feeling, and an anticipatory stomachache.

For drinks: matcha martini with a twist, Bloody Mary, pistachio espresso martini. For apps: miso and truffle deviled eggs, gochujang-glazed chicken wings, tamarind and yuzu ceviche. For an entree: mala rose pasta, chicken pasta with a pistachio cream sauce, yuzu-and-miso-glazed salmon. And for dessert: miso-caramel brownies, turmeric and ginger ice cream, pistachio tiramisu.

I skipped lunch in anticipation of my elaborate meal, which I had shopped for the night before after solidifying my scientifically designed, flavourmaxxed menu: a “sweet heat” beet salad, a favorite of Palank’s; salmon glazed with miso and gochujang, instead of yuzu (which I could not find at the nearest Whole Foods); and brownies with a miso-caramel drizzle.

I took some creative liberties: I plated my beets with a swirl of labne, instead of goat cheese, adding sumac and lemon in addition to the requisite drizzle of hot honey. To my miso-gochujang marinade, I added a dash of sesame oil. I asked my boyfriend, David, to mix a classic Paloma but to add coconut water, a New York Times recipe.

I added, too, jasmine rice with scallions and butter, and roasted broccoli finished with a tahini-lemon-garlic sauce.

As I ate, I realized that I had expected to be overwhelmed, but everything on my plate just tasted like good food. The salmon had a deep umami flavour with just a little heat; the tanginess of the labne, boosted by the lemon and sumac, was the perfect accompaniment to the beets.

Still, by the time I was adding a sprinkling of flaky Maldon salt onto my miso-caramel brownies, I had begun to feel a wave of fatigue, not just with flavour but with life. Even though Palank had promised me I would seem elegant and cultured to my friends, I had the hazy shame of trying too hard.

My guests appeared to be enjoying themselves, though. And Kevin made a remark that I tried to take as a compliment — or at least receive neutrally.

Cleaning his plate, he told me I had made the “perfect millennial meal.”