What India needs is a political pivot away from emotional appeals to the poor, especially in the agricultural sector, and a focus almost exclusively on urban interests. The future of the rural and agricultural poor lies in aggressive urban growth, not minimum support prices (MSPs) or subsidies. India needs a new and sensible urban, and urban only, party. The hybrid parties, who have one foot in urban areas and another in rural, and who try to be all things to all people, have failed in their urban missions.

Why an urban party? Several reasons.

One, urban areas are where new jobs in manufacturing and services will be created if enough investments are made in infrastructure, coupled with massive doses of deregulation. A World Bank argues that “urbanisation leads to concentration of economic activity, improves productivity and spurs job creation, specifically in manufacturing and services” which then has the “potential to transform … economies to join the ranks of richer nations in both prosperity and livability.”

Two, more Indians probably now live in urban or semi-urban areas, though official statistics don’t reflect this. A World Bank on south Asia’s urbanisation trends uses an alternate measure called Agglomeration Index and that “the share of India’s population living in areas with urban-like features in 2010 was 55.3 per cent.” Other put India’s urban population at 12 per cent more than the official figures (ie, around 44 per cent). This compares to an official urban share of the population of just over 31 per cent in the 2011 census, suggesting the likelihood of “hidden urbanisation.” The Agglomeration Index uses tools like satellite imagery and night lights to see how closely people are packed in urban-like habitats. If this is true, we must be nearly 60 per cent urban now, while some of the unrecognised towns and “rurban” areas continue to grow quietly, but robustly, in numbers.

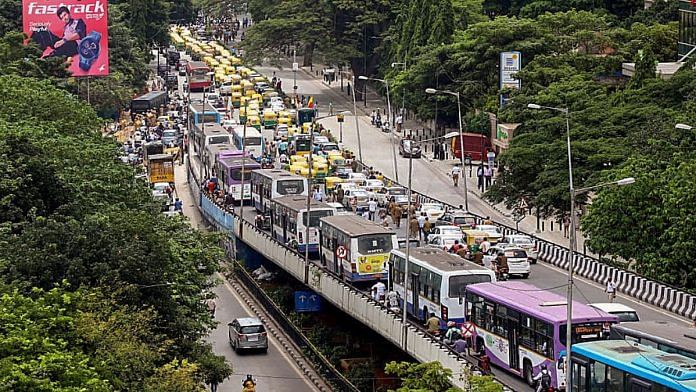

Three, state revenues are largely dependent on urban areas, but the resources generated by urban areas do not get substantially re-invested there. Take Bengaluru, India’s ‘Silicon Valley’. It generates, but it has terrible infrastructure, pot-holed roads, drying lakes and a serious water crisis. How is Bengaluru going to extract more money for investing in infrastructure and jobs when its wealth is being used to give free bus rides to women and endless doles to the rural millions? In an ideal situation, if the city could raise its own revenues and had a higher share of devolution from the state, the mayorship of Bengaluru would be a more coveted position than Chief Minister of Karnataka. But that is precisely what our farmer-loving, rural rhetoric-driven politicians dread.

An urban party focused only on urban interests would, hopefully, begin to correct this imbalance. Right now, politicians elected from rural redoubts use urban wealth to feather their own nests or sprinkle largesse on their rural voters, spending minimally on urban infrastructure. While the southern states are quick to claim that they contribute more to the central exchequer than what they receive, they do not apply the same logic to their own urban areas, whose resources are diverted for purchasing votes elsewhere.

Clearly, there is a strong case for paring down the Union and State lists in the Constitution to create a new Local Bodies List with exclusive powers. While many of the powers in the Concurrent list can be divided between Centre and states, the new Local Bodies List must give cities legislative and taxation powers of their own apart from hand-me-downs from the state governments.

The irony is that many parties which began with urban bases have now abandoned their original voters to court the ruinous rural vote. I say ruinous not because the rural and agricultural poor do not need help—they surely do—but because there is no economic nirvana in investing too much in agriculture. These investments must come from new agro-based entrepreneurship and the private sector resulting from deregulation. Agriculture needs to be freed from the clutches of endless subsidies and opened up for corporate and other investment, leaving the surplus labour to find jobs outside agriculture, which means migrating to cities. The only freebie worth having is to give transitional support to enable this shift from rural to urban labour. Once again, this calls for investment in urban areas.

The Aam Aadmi Party is a prime example of a city-based party that, through over-ambition on the part of its leadership, began courting farmers in Punjab and elsewhere to spread its wings. If it had only focused on MDGA (Making Delhi Great Again), the BJP would never have regained traction there. The BJP, which was once more urban than rural (the “Brahmin-baniya party” of yore), now keeps harping on the Annadata (ie, farmers) and the garib, thus diluting its original urban bias.

There is thus a clear gap in the political spectrum. A truly urban party would be able to achieve many things that broader-tent parties cannot. For example, they can get the urban vote out, currently missing in action due to apathy. Next, they can take strong postures against, say, the bullying by rich Punjab farmers who demand MSPs for all crops, and total commitment from the government to purchase all produce at MSP. They have been trying to invade Delhi to create political mayhem, but luckily the central government did not allow them to do so, so far. But the Centre has also been unable to negotiate a sensible deal with them.

A truly urban party would be able to mobilise urban voters against such bullying, even while negotiating better prices for agri-produce. Reason: urban areas represent the ultimate market for agri-produce, and an urban party can—conceivably—negotiate better prices with farmer producer organisations to benefit both producers and consumers; unlike the present situation where middlemen rule the roost. Even without constitutional changes, an urban party can also demand, and get, more powers from state governments.

India’s present and future are urban. We need political parties that can hasten this transition.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)