Former Indian High Commissioner to Pakistan, Satish Chandra, has strongly backed the government’s decision to suspend the Indus Waters Treaty in response to the Pahalgam terror attack, calling it a “Brahmastra” that could inflict long-term and “terrible” consequences on Pakistan, a country he described as heavily water-stressed.

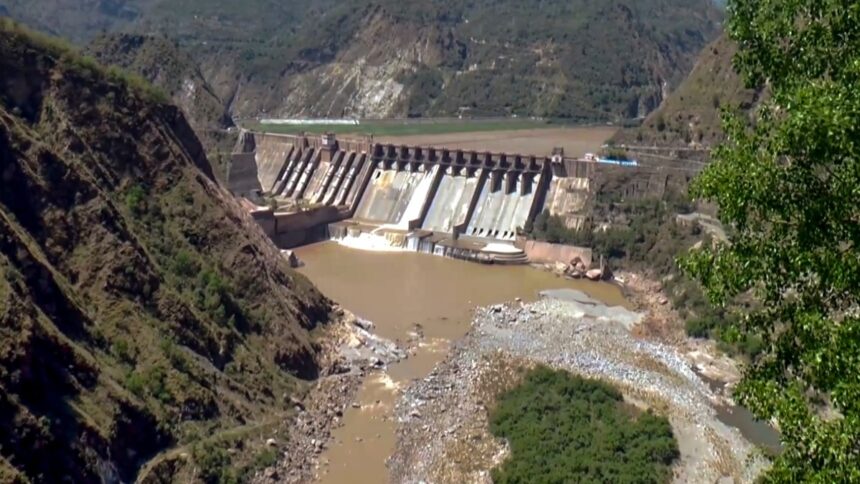

“Actually this move is a Brahmastra. Because the dependency of Pakistan on water is huge. It’s actually much more than ours even. They are a water-scarce country. And if what we have done is taken to extreme limits it will cause extreme pain even disruption in Pakistan,” Chandra said while speaking to StratNewsGlobal’s Nitin Gokhale. “This has been an excellent move. This treaty was overly generous to Pakistan. India has 40% roughly of the catchment area of the Indus basin. But under the treaty, we are providing Pakistan with as much as 80% of the water. And keeping only 20% for ourselves.”

He added that even India’s legitimate share of water could help resolve shortages in northern India, while any restriction of flows to Pakistan could severely hit its already strained irrigation-dependent agriculture.

Chandra criticised the treaty for being fundamentally imbalanced and unfair to India, noting that “all the obligations are on India” despite being the upper riparian country. He cited decades of Pakistani obstruction, ranging from prolonged delays to frivolous objections over Indian hydroelectric projects — even on rivers allocated to India.

“One of the projects with which I dealt with in the 1980s was a very small project called the Tulbul navigation project…they objected to it and the project never got off,” Chandra recalled. He also pointed to the Salal hydroelectric project which was conceived in 1920, cleared in the 1960s under the treaty, but only commissioned in 2005-2007, after “10 to 15 years of delay” caused by Pakistan’s objections.

The former envoy underscored that India had paid a heavy price for a treaty that was supposed to improve bilateral ties but failed to deliver. “This treaty hasn’t achieved one of the things that perhaps Nehru had in mind. He (Nehru) probably had in mind that this (treaty) will improve the relationships with Pakistan. In fact to our chief negotiator who wrote a book on this, Nehuru said – ‘we have got nowhere’. This meant that he (Nehru) was very disappointed at the state of relation. It has not improved relations with Pakistan.”

Chandra described India’s contributions at the time of signing as overly generous — pointing out that India paid $175 million to Pakistan, contributed to the Indus Basin Fund, and financed the construction of hundreds of miles of canals in Pakistan, some with greater capacity than the Potomac.

On the legal aspect, Chandra stressed that the treaty lacks an exit clause, making its structure rigid and outdated. However, he noted that international law allows a country to withdraw from a treaty if “circumstances change so drastically that a treaty becomes difficult to implement.”

These changed circumstances, Chandra said, include population growth, climate change, rising domestic needs, and cross-border terrorism. “Pakistan hasn’t come back to India on renegotiation. So it is already in breach of the treaty itself,” he added.

He praised the Indian government’s decision and the careful wording of its announcement: “I am delighted that we have placed this treaty in abeyance. It is an excellent move. The language we have used is very time-elastic. No court can really say that what India has done is wrong because the circumstances are totally different from the time when it was conceived in 1960.”

Chandra concluded that the Indus Waters Treaty, “badly drafted” and used by Pakistan in bad faith, has long served as a tool to delay Indian development and must now be reconsidered in light of national security and sovereign interests.